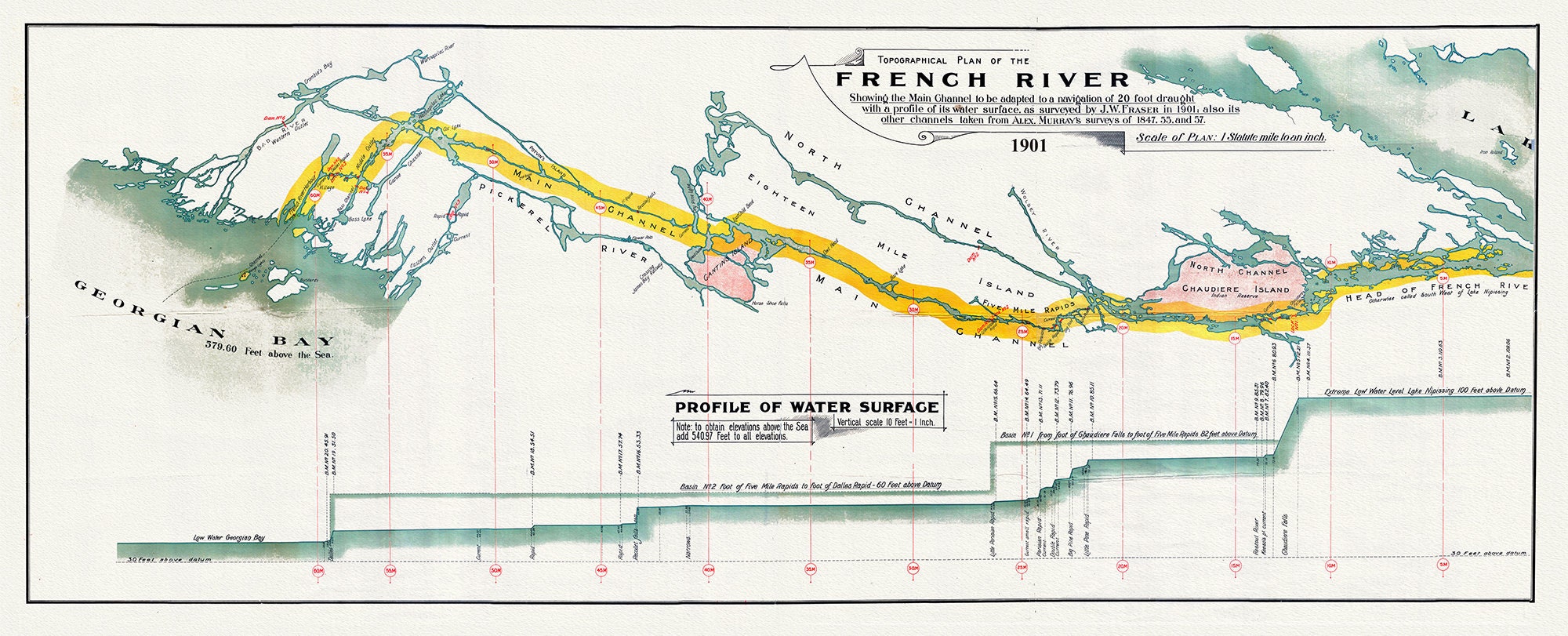

French River Canal, main channel to be adapted to a navigation of 20 foot draught, 1901, map on heavy cotton canvas, 18x27" approx.

$44.93

In the history of humankind, it is difficult to pinpoint events that changed the course of history. Generally many series of events lead to momentous circumstances. Never mind Northern Ontario, Canada would be a different place if the Georgian Bay Ship Canal had become a reality.

Ships the length of two football fields laden with grain from the prairies using the French River and Lake Nipissing? This vision at one time almost became a reality. Highway 69 may not have become a reality.

The proposed Georgian Bay Ship Canal was promoted as a project with the magnitude of a Panama Canal. This waterway would have allowed Great Lake freighters to travel directly from Lake Huron to Montreal.

As early as 1837, pre-Confederation, the Family Compact members of the Assembly of Upper Canada ordered a survey of the possible route. The War of 1812 was still fresh in the minds of the politicians and an inland waterway would skirt American influence.

Canada's first Prime Minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, recognized the potential of the project: "The Ottawa Ship Canal and the Pacific Railroad must be constructed and no voice should be raised against the great national work which would open the western states and the colonies to the seaboard.”

There were a number of advantages claimed for the proposed ship canal. For one, it was the shortest route from the upper Great Lakes to the ocean harbour of Montreal.

THE WAY

The surveyed waterway was essentially a scheme to canalize a number of rivers and lakes which exist along the old voyageur fur trading route of the French, Mattawa and Ottawa Rivers.

In 1904, the Department of Public Works was instructed to undertake a detailed field study of the route. The finished report of 1907 included a geological survey of rock formations, depth soundings of Lake Nipissing and engineering details of dams and canals. The original 600 page document contains a wealth of detail and gives evidence of an impressive study. The navigable waterway was estimated to be 70 kilometres long. The French River, including the creation of a lock and dam at the Chaudiere Rapids, would be an important bridging point which would allow the lake level to rise. This was necessary to accommodate ships that would have a draft of almost seven metres deep. The high steel gates, at the Big Chaudiere Dam on the French River, were designed in preparation for such a canal. Take a look this summer as you travel by boat or canoe through the Upper and Lower French River.

From the report, the engineers stated that a total of eight single and three double locks were needed to connect the various bodies of water. There would have been 11 changes of water levels ranging from three to 19 metres. In conclusion, the report stated, "...the probable cost of a deep waterway can be established for $100 million...the work taking 10 years to complete."

The chief engineer for the project promised that a "630 ft. (approximately 200 metres) freighter, moving at 12 miles per hour could navigate the entire distance of the passage in 70 hours."

PANAMA CANAL

What we fail to realize when looking at this project, is that the magnitude, was on the scale of the Panama Canal. The Welland Canal would pale in comparison. The Georgian Bay Ship Canal was one way to foster nationalism and an economic response to the demands of the new frontier, the prairies.

With the movement of cattle, grain, lumber and minerals through the Nipissing Passageway, a significant economic impact would have been created. A new port on Georgian Bay would have become the logical location for a variety of processing plants. Goods manufactured in the area would have been transported to lucrative Southern Ontario markets.

The mega project's demise can be attributed to the might of the powerful railway conglomerates of the day that had their own visions of transportation. The technology to construct the plan was in place, but the railway companies thought it was best to lay down railway tracks, rather than try to blast through the Canadian Shield. Canals that had previously been constructed, throughout North America, were not turning profits. It would have taken billions of dollars. Another reason, overlooked by the early surveys of the 1850's, was identified in the field work of 1906. The immense physical changes were great, not unlike the scope of the James Bay power project.

Apart from practical considerations, the political ramifications certainly were overwhelming. The competition between Toronto and Montreal as Canada's leading centre, was a determining factor in turning support away from such a project. No project that would benefit the development of Montreal would ever be allowed.

In 1953, work began on the St. Lawrence Seaway. It was a longer distance than the Georgian Bay Ship Canal and involved much American ownership. The dream of a once, navigable waterway, from Lake Huron to Montreal was dead.

Don’t miss this amazing display of the fascinating history and geological features of the French River! You can weave your way through time as you experience the life of early Aboriginal people, explorers, missionaries and voyageurs.

We celebrate the vision of Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, whose Canadian Pacific Railway forged the steel belt that bound young Canada together.

At the same time, we have to be thankful that another, equally grand, scheme of our forefathers never got off the drawing board.

With Ontario’s Welland, Rideau and Trent-Severn canals all up and running, it was inevitable that eyes would be cast northward toward yet bigger game. In 1894, a group of promoters, whose research must have been limited to a glance at a small-scale map, formed the Montreal, Ottawa & Georgian Bay Canal Company. The aim was to open a direct steamboat link between Montreal and the upper Great Lakes utilizing the Ottawa, Mattawa and French rivers. In response to effective lobbying, the Canada Department of Public Works commissioned an engineering survey of the proposed canal. In 1908, following an exhaustive examination of the route, the government published its findings.

The study possibly had an impact upon Parry Sound, in the form of the CXL (later CIL) dynamite plant that opened at Nobel a decade or so into the 20th century. As it turned out, Northern Ontario’s mining boom would absorb much of the plant’s production, but the expectation of an even bigger demand for canal building could have figured in Nobel’s birth.

For building the Montreal, Ottawa & Georgian Bay Canal, had it gone ahead, would have consumed an awful lot of dynamite. It was to be no mere barge canal. Specifications called for a minimum depth of 22 feet, sufficient to accommodate large lake freighters. Detailed large-scale maps forming the heart of the report illustrate the complexity of the job. Scores of control structures would have to be installed to get steamboats up into Lake Nipissing then down to Georgian Bay (I wanted to count the locks on just the 60-mile-long French River section, but that particular map has disappeared from the set lodged in the Parry Sound Public Library).

The proposed canal never went ahead for several reasons, all of them rock solid. The estimated cost was an astronomical hundred million in 1908 dollars. Even if the builders had succeeded in molding the stubborn Precambrian Shield to their purposes, the time lost by a steamer negotiating locks surely would negate any advantage offered by the more direct route. Finally, a Royal Commission examined the plan and set it aside. This was in 1914, the year the Great War broke out and consumed all the nation’s energy for the next four years. By the war’s end, canal building of all kinds was passé and the Montreal-to-Georgian Bay engineering study began gathering archival dust.

However, the French River does have a limited steamboat history, thanks to some small craft that plied those waters in the pine-logging era. The first such vessel that I know of is the Alligator, the prototype of a fleet of log-warping tugs invented and produced by the firm of West & Peachey at Simcoe, Ontario. Basically a wooden scow equipped with a 12-horsepower steam engine and propelled by sidewheels (later models were screw-driven), the craft was designed to drag booms of sawlogs across lakes employing a winch wound with a mile or so of steel cable. In addition to warping large log booms across expanses of dead water, it could winch itself over portages, an advantage on rapids-strewn rivers like the French.

This map has been carefully restored and recreated onto a heavy 100% cotton canvas and not a fragile paper. My maps can be easily rolled to be presented as a gift or retrieved from storage to be unrolled to reveal a fascinating historical conversation piece. Search your family history and geneology.

The map appearance I am trying to achieve is that of a map that has been bound in an atlas that has been lovingly cared for over the last 200 to 400 years, with the original hand coloring. On certain monitors and smart phones, colors may look excessively bright because your screen is lit from behind. I can assure you that the colors will not be so garish when you receive your map. Instead you will be appreciative of the heft and quality of the highly textured canvas, which can sustain a certain amount of rolling up and abuse. These were designed to be heirlooms.

Your item has a durable protective coating which would allow it to be framed without heavy, glaring glass. Feel free to touch it!

Frame it yourself! Not all that hard to do. A rustic looking frame will enhance its appearance or just use the 4 map pins, provided at no charge, to tack to your wall or message board.

Are you looking for a specific locale? We have Everywhere! Just send us your inquiry.

Desire a different size? Send us your requirements. We can select a print for you that fits perfectly into an old frame you might have in your attic or garage!

All unit measurements are approximate, most usually 20 x 25-30"

Shipping from Canada

Processing time

2-3 weeks

Customs and import taxes

Buyers are responsible for any customs and import taxes that may apply. I'm not responsible for delays due to customs.

Payment Options

Returns & Exchanges

I gladly accept returns and exchanges

Just contact me within: 14 days of delivery

Ship items back to me within: 30 days of delivery

I don't accept cancellations

But please contact me if you have any problems with your order.

The following items can't be returned or exchanged

Because of the nature of these items, unless they arrive damaged or defective, I can't accept returns for:

- Custom or personalized orders

- Perishable products (like food or flowers)

- Digital downloads

- Intimate items (for health/hygiene reasons)

Conditions of return

Buyers are responsible for return shipping costs. If the item is not returned in its original condition, the buyer is responsible for any loss in value.